The latest industry disruptor combines BEV and PHEV to tap the range/cost sweet spot. By Megan Lampinen

Range anxiety remains one of the biggest obstacles in the shift to electric vehicles (EVs). For drivers without access to a home charger or those that travel long distances, lack of public charging is a huge deterrent. Add to that continued price premiums over gasoline and diesel models and it’s understandable why EV volumes have fallen short of projections. Recently, an alternative approach to electrification has been gaining ground and could prove a major industry disruptor.

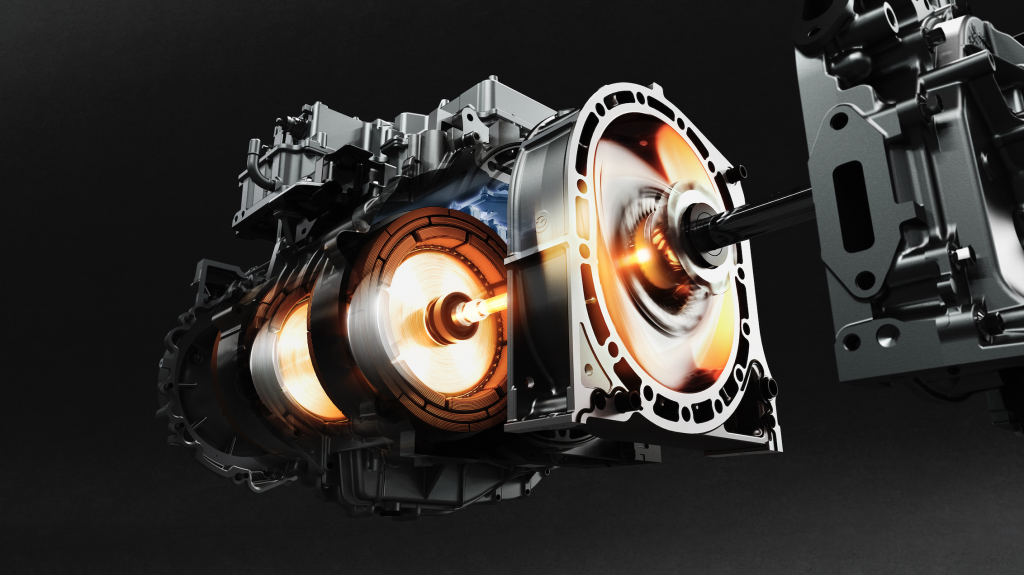

2024 saw a number of global automakers dial back or postpone EV launch plans in favour of extended-range EVs (EREVs). This is a form of plug-in hybrid EV (PHEV) in which a small combustion engine is used solely as a generator for the battery, with no connection to the drivetrain. Like a traditional PHEV, an EREV can be plugged in to charge the battery while the engine is refuelled with gasoline. But unlike traditional PHEVs, EREVs can travel long distances on battery power alone: an average PHEV will offer an all-electric range of 20-40 miles, while an EREV could offer something closer to 200 miles. Supported by the engine, a model’s total range could easily be double that—Li Auto offers EREV models boasting total ranges in excess of 800 miles.

EREV technology is not new. A handful of models debuted alongside the initial mass market EVs about a decade ago, but they failed to gain traction among the wave of tech-savvy, eco-driven early adopters. However, EREVs are now undergoing a renaissance as an alternative to pure BEVs while the world comes to grips with charging requirements and affordability.

China leads the way

China is the world’s largest EV market and leads the charge on EREVs. Boston Consulting Group reports that both PHEVs and EREVs combined recorded a CAGR of 104% in China between 2020 and 2024, compared to a 55% for battery EVs. Bloomberg figures show that EREV sales alone more than doubled in China over the past year and currently account for roughly 30% of the country’s PHEV market.

Several brands have been competing in this space, though Li Auto is the global EREV leader in terms of sales. Many more are set to join the trend, and not just in China. The past year alone has seen the likes of Xpeng, Volkswagen SAIC, Stellantis, Lotus, Hyundai, Ford, Mazda, and Scout Motors all announce new or additional EREV production launch plans for China, the US, and Europe.

Boston Consulting Group predicts that EREVs “will likely play a greater role going forward in the US and, before long, in the EU.” McKinsey makes a similar conclusion. “In the short term, we expect EREVs to be concentrated in China, but the expansion of Chinese OEMs into new markets and EREV investment by [other] OEMs means we will likely see EREVs taking more market share globally in the medium term,” says Paul Hackert, Senior Expert, Product Development & Procurement at McKinsey. That said, regulatory differences could hold back the segment’s potential in Europe. “In the US, current regulations give partial zero emissions credits for EREVs,” Hackert tells Automotive World. “In Europe, existing regulations require pure battery electric vehicles (BEVs) by 2035, limiting the long-term advantages of EREVs in that market.” China’s broader New Energy Vehicle policy recognises EREVs equally alongside PHEVs and BEVs.

A new demographic

A late-2024 survey from McKinsey found that a sizeable percentage of respondents would consider an EREV for their next vehicle purchase if one were available. Among the 2,800 new-car buyers surveyed in the US, 18% were “very interested in purchasing EREVs” once the technology was explained to them. “That was a lot higher than I expected,” notes Hackert. Across the US consumer group and the 2,300 buyers surveyed in Germany and the UK, two-thirds noted an intent to purchase an internal combustion engine (ICE) or hybrid vehicle in the absence of an EREV option. McKinsey concludes from this that EREVs could motivate more ICE vehicle owners to move to electric.

“EREVs hit a sweet spot with consumers when it comes to electrification,” observes Anna-Sophie Smith, Leader for Mobility Consumer Insights at McKinsey. “They appeal to this group that is open to electrification but may have range anxiety or may not have the opportunity to charge at home. Fast charging and the longer ranges possible with the EREV’s backup generator really hit some of the existing concerns. That is an important consideration, especially in Europe, which faces a 2035 deadline for zero emission vehicle-only sales. An EREV on the market now can help people transition to electric.”

The sweet spot

EREV technology could potentially apply to almost any vehicle segment, but it has primarily been used with SUVs and pick-ups so far. “Some vehicle segments that have a greater percentage of longer distance driving customers—such as full-size work pick-ups or vans making multiple daily customer stops—may have a higher than average demand for EREVs,” suggests Hackert. “We are seeing more pick-ups in the EREV space, perhaps because it’s easier to package a larger battery and an engine in this vehicle class.”

Stellantis intends to introduce EREV technology on the Ram 1500 Ramcharger pick-up, while VW’s Scout Motors will use it for an upcoming range of rugged SUVs and pick-ups. Ford Chief Executive Jim Farley has also thrown his support behind the technology for certain vehicle segments. Speaking to analysts in the company’s Q4 2024 earnings call in February 2025, Farley noted that EREVs could be the key to electrifying affordably the big trucks that American consumers favour. “They love big trucks and they love the feeling of electric, but they just can’t get it,” he told analysts. “It’s US$30,000 or US$40,000 too expensive for these big vehicles. This technology gives them the electric experience without the range anxiety.”

That’s down to using a smaller battery than BEVs. There will always be a compromise between range and cost, but McKinsey suggests that there could be a sweet spot. By targeting 100-200 miles of EV-only range and total range of 350-600 miles depending on customer segment, it believes EREV costs should fall between a similar sized ICE and a BEV. “That would satisfy almost all customers’ daily commute and some longer commute requirements,” asserts Hackert. McKinsey’s Madhumitha Aravanan, an Asset Leader and Portfolio Manager, points out that there is “no real convergence yet on what the capacity of the battery plus the engine should look like.”

In the future, EREVs could potentially lose some of that cost benefit as battery costs decrease. They could also take a hit should the industry see any other major advances in battery technology that somehow reduce their advantage over PHEV.

Outlook

McKinsey believes that EREVs could grab a 2.5% share of the global passenger vehicle market by 2030, though Hackert stipulates this figure is “actively changing as automakers shift production plans.” Market Research Intellect predicts that the global EREV market could be worth US$518bn by 2031. While the potential is there, lack of consumer awareness and a scarcity of models are major constraints to uptake.

“People are still very confused,” cautions Smith. In McKinsey’s US consumer survey, 27% of respondents thought ICE was a more sustainable option than EREV, BEV or other hybrid forms. 48% agreed with the statement ‘I’m overwhelmed by the number of powertrains currently available to choose from’. Moving forward, automakers will need to put in a concerted effort to educate consumers and clearly communicate the benefits of the technology.

“The industry has come to the realisation that public charging systems aren’t where we want them to be,” concludes Hackert. “EVs are still priced at a significant premium over ICE…It could be an interesting time to invest and make EREVs available. There are trade-offs and risks.”